- Case-Based Roundtable

- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Buy-and-Bill

Article

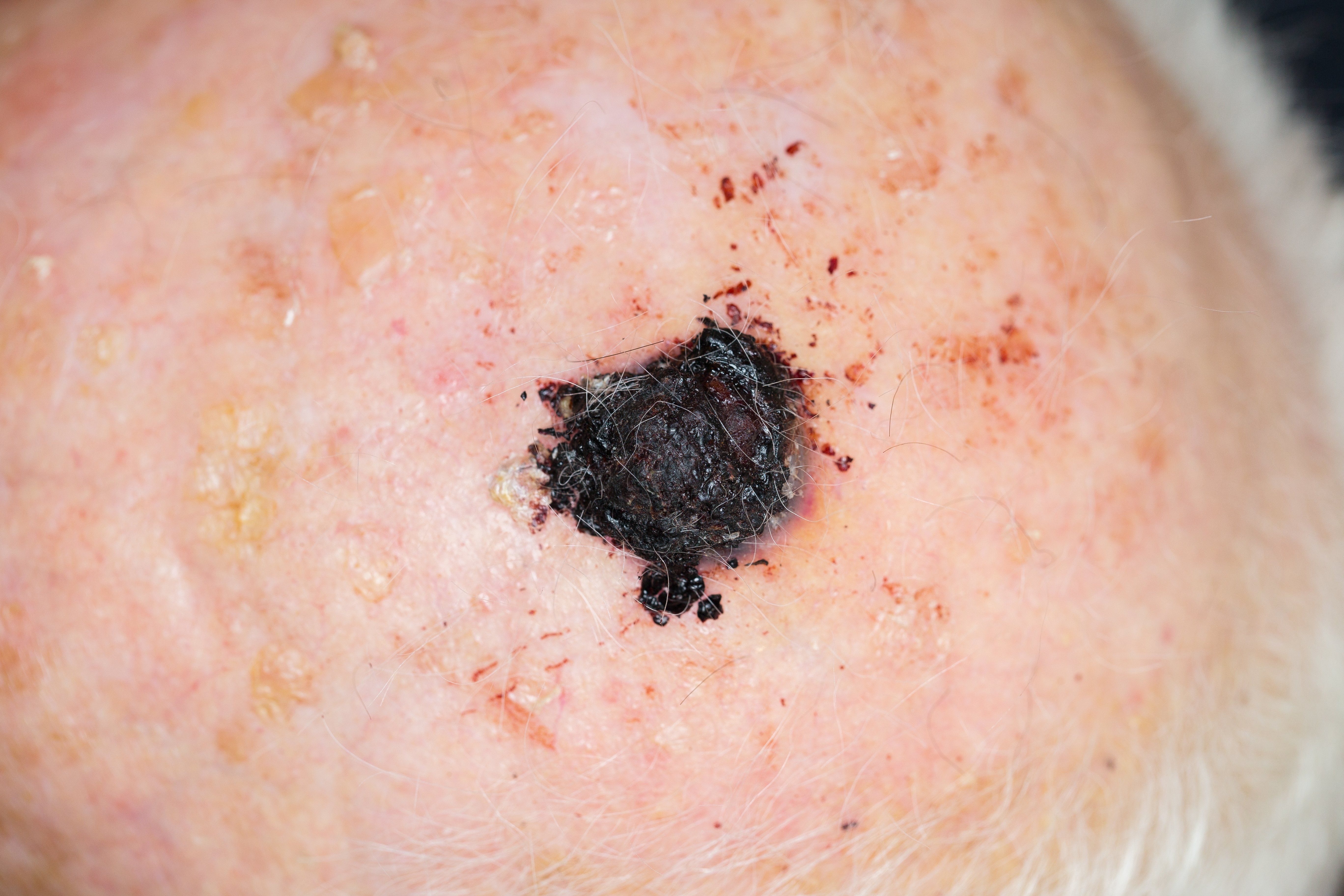

Treating melanoma: The cost of care vs the value of life

Author(s):

What is a life worth? Does it come down to dollars and cents? A recent study examines these questions in light of current and projected costs of melanoma treatment.

What is a life worth? Does it come down to dollars and cents? A recent study examines these questions in light of current and projected costs of melanoma treatment. (lavizzara - stock.adobe.com)

What is a life worth? Does it come down to dollars and cents? Should it be measured by quality of life? Should economic burden be considered?

These are not easy questions, but in a November 21 analysis published in JAMA Dermatology, Ivo Abraham, Ph.D., of the University of Arizona shows that the cost of a treatment that could add one year of progression-free survival for patients with advanced and unresectable melanoma could be about $1.6 million-an amount most payers are willing to pay.

“These numbers are very high and are well outside the willingness of payers to pay. In the end, it seems to all consistently converge around $1.6 million per unit of improvement,” he said in an interview with Dermatology Times.

The analysis (DOI:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3958) compares the cost of ipilimumab monotherapy with a combination therapy of consisting of ipilimumab and talimogene laherparepvec which were administered in up to 100 patients in a single phase two trial. Although he and his team found some benefit-objective response rates 18% (18 of 100 patients) and 38.8% (38 of 98 patients), respectively-from an economic standpoint, it doesn’t appear to be beneficial. The cost of combination therapy was $494,983 per patient compared to $132,950 with monotherapy for a cost difference of $362,033.

“As an absolute number, you could say the difference of 21% in objective response rate is really a lot. But in reality, this is not an impressive result because the ipilimumab-only objective response rate was low at 18% and the talimogene laherparepvec plus ipilimumab objective response rate was very modest at 39%,” he said.

RE-EVALUATING THE COST OF TREATMENT

The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2018, there were 91,270 new cases of melanoma and 9,320 deaths (DOI:10.3322/caac.21442). And, according to a report in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (DOI:10.1093/jnci/ djq495), the national cost of melanoma treatment is projected to reach $3.16 billion by 2020, which is up from $2.36 billion in 2010.

“Melanoma is one of these diseases where for so long we had virtually no progress in treatment options, but now we have several options,” Dr. Abraham said.

For advanced and unresectable melanoma, these treatment options include BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenibmesylate and encorafenib), immune checkpoint inhibitors (ipilimumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab), and oncolytic virus (talimogene laherparepvec). Treatment can be as monotherapy, but research is beginning to indicated that combination therapy is more effective for some patients.

“The treatments we have now are much better than what we used to have. These drugs are very expensive to manufacture and their studies are very expensive to conduct. We have to come to grips with the fact that these drugs are going to cost more. The balance we now need to find is what is reasonable to charge and what is too much,” Dr. Abraham said.

Because patients with cancer tend to be more accepting of adverse events in return for positive outcomes, economic evaluations are evolving so that these inherent adverse events are not penalized, but rather are considered as part of a complete picture with clinical outcomes.

“For economic analysis of drug treatments, we are sort of being forced to still think in terms of the established or classical pharmacoeconomic methods that come out of an era of small molecules in which drugs are relatively simple to make, versus biologics or oncolytic virus treatments for melanoma,”

Dr. Abraham says he and his colleagues are struggling with the fact that these classic analyses have low cost thresholds.

“It is also important to have economic evaluations that are conducted independently from industry but also from payer organizations. Industry has an interest in coming up with results that portray favorably upon them. The same holds true for payers,” he said.

“We do not consider pharmacoeconomics as a way to set policy, but to inform policy. Our analysis is a way of stimulating and informing the debates about the value that we may or may not get out of these treatments,” he said.

In 2018, the President’s Cancer Panel, an NIH group formed to examine out-of-pocket costs associated with cancer treatment, recommended (1) that cancer treatment pricing be replaced with value-based or outcome-based pricing, (2) the adoption of payment models that incentivize clinicians and health care organizations to use high-value drugs, and the group recommended that (3) patients be encouraged to choose treatments with high-value drugs.

But in this article, the authors state that we need to move beyond focusing on cost and instead, “adopt a workable definition of value to operationalize and quantify value. In 2010, Porter et al. writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggested that value be defined as the “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” which is concept the authors of this new study described as one that should be explored further. The American Society of Clinical Oncology, the European Society for Medical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network measure value by clinical benefit, toxicity, and quality of life. The American Society of Clinical Oncology includes actual costs.

THE FINDINGS

The economic model used in this study consisted of the cost of treatment, medication administration, monitoring, management of grade three and four adverse events for each of the two treatment arms, utilities and disutilities.

The analysis concluded that for combination therapy, the cost to gain just one additional progression-free quality-adjusted life year (QALY) was roughly $2.2 million, compared to about $2.1 million for one additional progression-free life-year or $1.6 million for an additional single patient to attain an objective response.

“These numbers are very high and are well outside the willingness of payers to pay. In the end, it seems to all consistently converge around $1.6 million per unit of improvement,” he said.

To reconcile the imbalance of cost and outcome, the investigators say that the price of the combination therapy must be drastically reduced or demonstrate another clinical benefit like increased overall survival.

Pricing of therapy that more closely matches the demonstrated effect should also be encouraged, so that price points align with their therapeutic benefit.

The economic construct of the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) may also vary by disease, treatment options and prognosis because the construct assumes that patient preferences, clinician treatment patterns and a payer’s willingness to pay are consistent.

Dr. Abraham says the standards of $50,000 to $150,000 for one additional QALY are unrealistic.

LIMITATIONS

This study was based on a phase two randomized, open-label trial, but it did not include survival data. There were other limitations of note as well, such as whether safety and tolerability measures were fair in this case.

“Several of the above clinically oriented frameworks, together with the QALY-based approach, consider safety and tolerability a negative that requires a downward adjustment of the benefits of a treatment. This overlooks the reality that most cancer treatments have more (and more severe) safety and tolerability issues compared with general medicine treatments. Therefore, applying similar utilities and disutilities for cancer as for general medicine ignores the fact that patients with cancer tend to be more willing to accept adverse events in return for effective treatment,” the authors wrote. Â

Reference

Almutain AR, Alkhatib NS, Oh M, et al. “Economic evaluation of talimogene laherparepvec plus ipilimumab combination therapy vs ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with advanced unresectable melanoma,” JAMA Dermatology, 2018 November 21. DOI:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3958 [Epub ahead of print]