- Case-Based Roundtable

- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Buy-and-Bill

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Off-label drug promotion or education?

Author(s):

How far can drug companies go with off-label promotion? Dr. Goldberg addresses this and more in his latest Legal Eagle column.

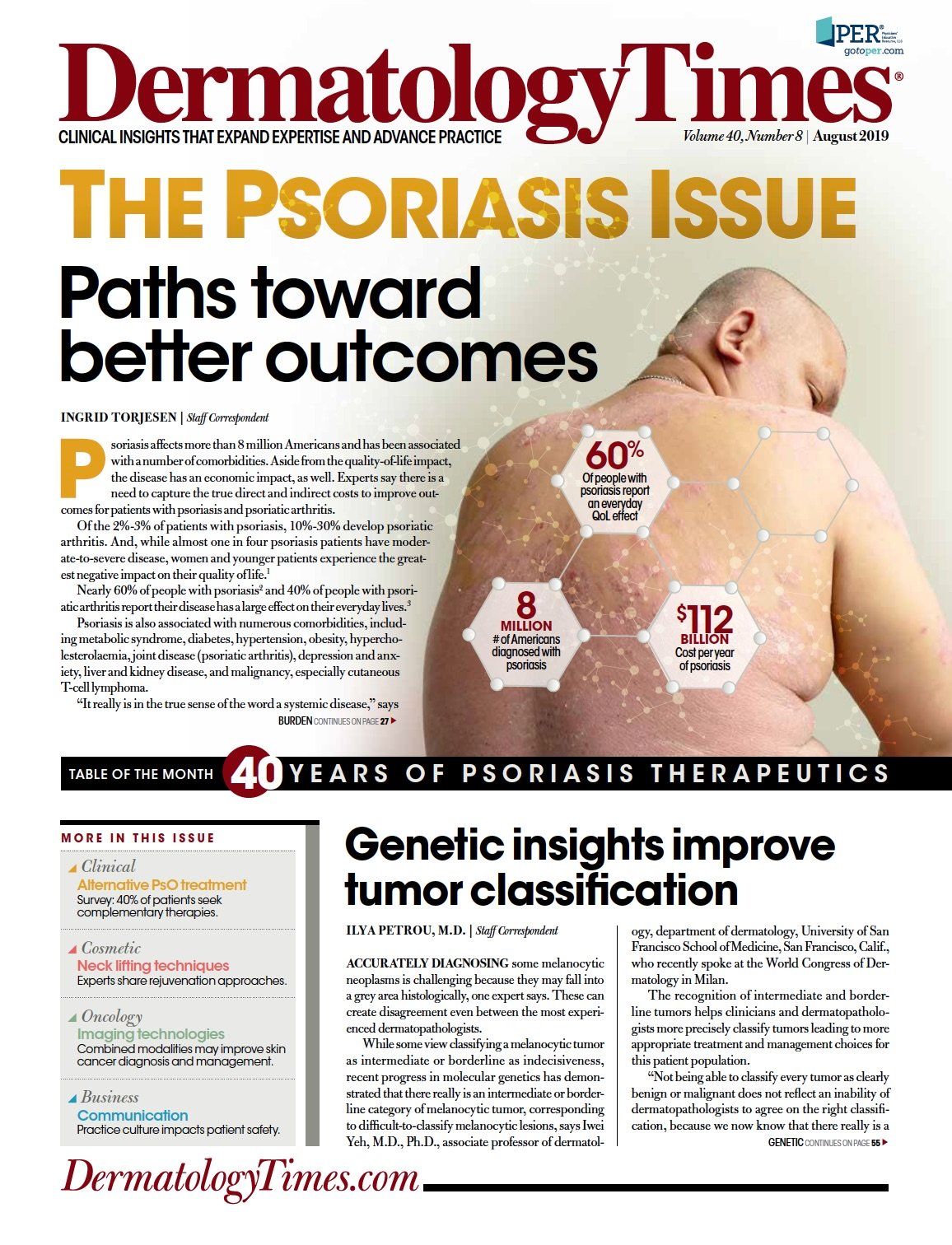

Since off-label uses are presently an accepted aspect of a dermatologist’s prescribing regimen, the open dissemination of scientific and medical information regarding these treatments is of great-import. (JJAVA - stock.adobe.com)

Dr. Goldberg

You are a member of your local dermatologic society and attend monthly meetings in order to obtain your desired CME credits. In order to finance the meeting and encourage attendance, the society has the monthly meetings financed by a prominent drug company.

The food is excellent, conforms to pharma guidelines, and the lecture very stimulating. The drug company provides journal articles from the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology at the meeting that document the off-label use of one of their newer biologic agents. You obtain CME credits, read the journal article, and begin prescribing the off-label medication. A fellow dermatologist tells you that the drug company is in violation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rulings against promoting off-label use. He contends you might also run afoul of the regulations.

The FDA derives its authority to regulate various aspects of the pharmaceutical industry from the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C., section 301. For a prescription drug to be distributed by a manufacturer in interstate commerce, the manufacturer is required to demonstrate that the drug is both safe and effective for each of its intended uses.

As part of the approval process, FDA also reviews the proposed labeling for the drug, which includes all proposed claims about the drug’s risks and benefits. The FDA will only approve a company’s new drug application if the labeling conforms to the uses that the FDA has approved.

In 1962, Congress determined that a manufacturer seeking to market or promote a product for an unlabeled use must resubmit the drug for another series of clinical trials similar to those from the initial approval. Off-label uses include treating a condition not indicated on the label or treating the indicated condition but varying the dosage regimen or varying the patient population. Manufacturer promotion of off-label uses constitutes misbranding and is in violation of the FDA statutes.

Since off-label uses are presently an accepted aspect of a dermatologist’s prescribing regimen, the open dissemination of scientific and medical information regarding these treatments is of great-import. The FDA acknowledges that physicians need reliable and up-to-date information concerning off label uses. FDA recognizes that sources for such information are varied and include CME lectures and seminars. It specifically recognizes that the need for reliable information is particularly acute in the off-label treatment arena because the primary source of information usually available to physicians - the FDA approved label - is absent.

Off-label prescription practices can be problematic and have, in some circumstances, proven harmful. Therefore, the FDA, has always been concerned about drug company promotion. How far can drug companies go with off-label promotion?

It was the Washington Legal Foundation that sought to set guidelines through a lawsuit they initiated. The Washington Legal Foundation was a non-profit public interest law and policy center that defended the rights of individuals and businesses to go about their affairs without undue influence from government regulators.In Washington Legal Foundation v. Michael A. Friedman, Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration and Donna Shalala, Secretary of U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Services, the Washington Legal Foundation contended that peer reviewed journal articles, as scientific and academic speech, are entitled to the highest level of First Amendment free speech protection. There should be no FDA restrictions on the dissemination of such materials. FDA claimed that journal articles represent commercial speech that is not as strictly protected by the First Amendment, as is non-commercial speech.

In analyzing the litigation, the United States District Court for the District Court of Columbia noted that the distribution of enduring materials and sponsorship of CME seminars does constitute speech and therefore is entitled to First Amendment protection.

What the court struggled with was whether manufacturer distribution of peer reviewed articles promoting off-label uses at CME seminars was pure speech, demanding near absolute free speech protection, or commercial speech that could be somewhat restricted.

The court, in its decision in July of 1998, noted that when considered outside the context of manufacturer promotion of their drug products, CME seminars, peer-reviewed articles and commercially available medical textbooks merit the highest degree of constitutional protection.

The question raised was whether speech that would be fully protected as scientific and/or educational speech can be transformed into commercial speech with a lesser degree of free speech protection, simply because a commercial entity seeks to distribute materials that would lead to an increase in sales of the product addressed in the speech. Such restrictions might be appropriate when public health is an issue.

The court decided that off-label articles, such as the one from the JAAD, represent commercial speech when distributed by a drug manufacturer at a monthly CME dermatology meeting.

The court then evaluated whether FDA’s ban of manufacturer’s distribution of off-label peer reviewed articles was appropriate. The court felt the absolute ban was more restrictive than necessary. The court noted that in the balancing act between free speech and restriction of First Amendment rights, it is always better to allow free speech.

The court would have no difficulty with the distribution of off-label journal articles from the JAAD as long as the drug manufacturer provides full disclosure.

The involved dermatologist has nothing to worry about.