- Case-Based Roundtable

- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Buy-and-Bill

News

Article

Partner Content

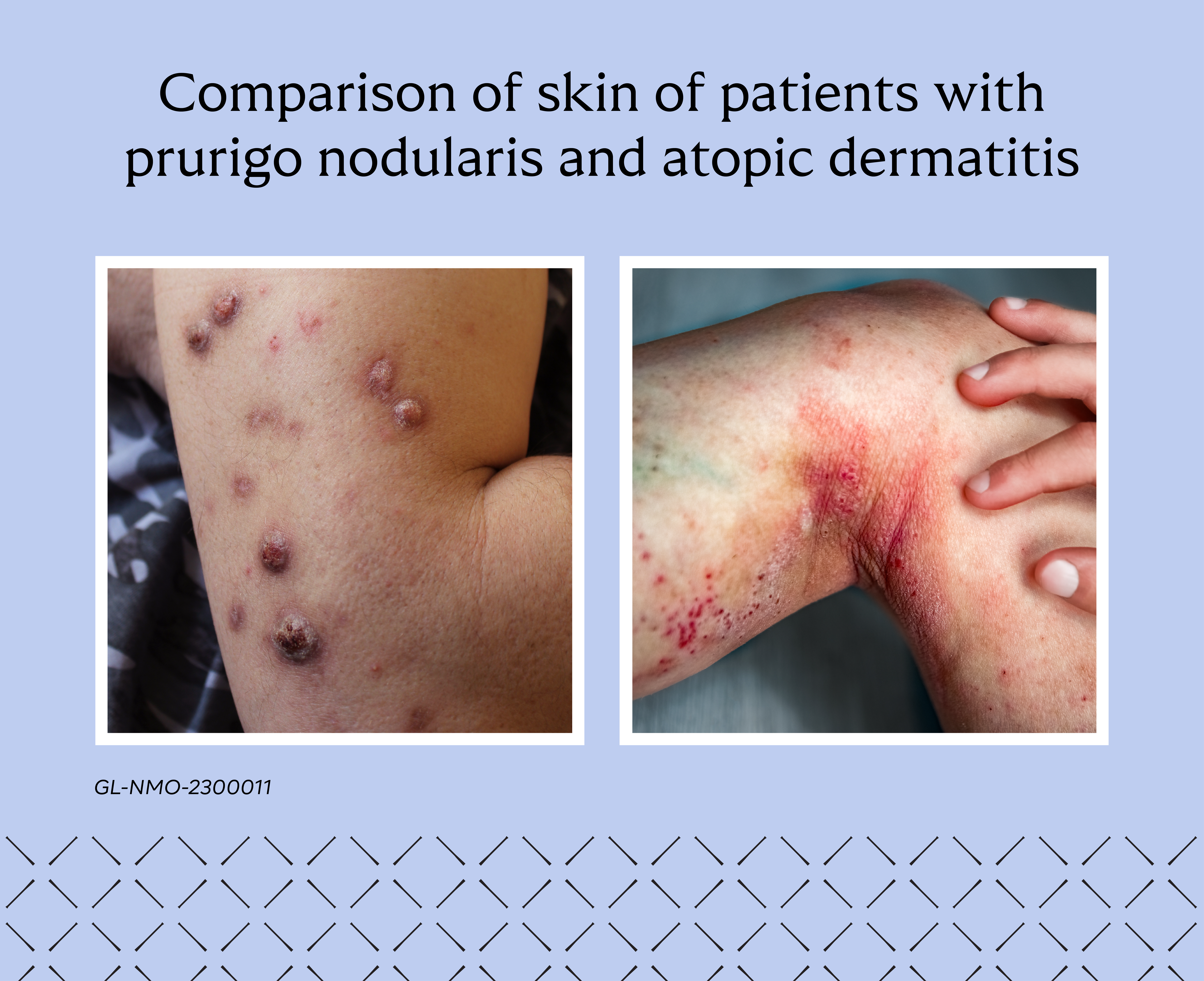

IL-31: An important neuroimmune cytokine in prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis

This article is authored by Dr. Baldo Scassellati Sforzolini, M.D., Ph.D., MBA, Global Head of R&D, Galderma and Dr. Christophe Piketty, M.D., Ph.D., Global Senior Program Head at Galderma. IL-31 is a neuroimmune cytokine that drives the most burdensome symptom in prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis, namely itch, and is also involved in skin inflammation and keratinocyte abnormalities.

Prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis are distinct inflammatory skin conditions which share a common symptom – chronic itch (pruritus). Itch is the most burdensome symptom experienced by patients with prurigo nodularis, and 80% of patients with atopic dermatitis describe itch as one of their top three most bothersome symptoms.1,2

In fact, recent research on prurigo nodularis presented at the 2023 European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) congress in Berlin has shown that the vicious itch-scratch cycle leads to insomnia, which is associated with the development of neurocognitive morbidities such as depression and anxiety. Researchers concluded that disrupting this cycle through rapid and sustained itch relief is crucial to restoring sleep quality in patients with prurigo nodularis and improving long-term outcomes.3 Compared to other dermatological conditions, prurigo nodularis is among the conditions with the largest impact on a person’s quality of life.4,5 Patients also suffer a psychological burden from having unsightly lesions on visible areas of the body, which can significantly impact confidence and social interactions.1,6 Scratched nodules can also bleed, increasing the risk of recurrent infections that cause additional burden.7

In atopic dermatitis, most patients also experience sleep disturbance and have a higher risk of developing mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction, and reporting suicidal ideation.8,9 Almost a third of adults with atopic dermatitis report that the physical appearance of their skin disease caused them to avoid social interactions, and many experience social stigma and isolation.8,9

Prurigo nodularis

Prurigo nodularis – a chronic, debilitating, and distinct neuroimmune skin disease characterized by the presence of intense itch and thick skin nodules covering large body areas – affects an estimated 5.5 million people worldwide, with up to 80% of patients suffering from moderate to severe disease.10-15 Prior to diagnosis, symptoms of prurigo nodularis are primarily managed with systemic or topical treatments to help reduce inflammation, itch, and the size and induration of skin nodules.16-19 The lack of standardized classifications of the disease and understanding of the pathophysiology of prurigo nodularis has led to poor management and suboptimal outcomes for patients.20-23

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a common, chronic and flaring inflammatory skin disease characterized by persistent itch and recurrent inflammatory skin lesions.24,25 Affecting more than 230 million people worldwide, it is a highly variable condition and associated with a significant reduction in quality of life and several comorbid conditions, namely mental health disorders and other autoimmune-mediated or immune-mediated diseases.

The role of IL-31

In the last decade, a small group of scientists dedicated their efforts to understanding the itch response and its drivers in inflammatory skin diseases. Their research was the first to indicate that interleukin-31 (IL-31), a neuroimmune cytokine, has a dominant role in the pathophysiology of prurigo nodularis and atopic dematitis.26,27 IL-31 is now widely accepted as the first known cytokine to bridge the gap between the immune and nervous systems and the skin – the body’s largest organ.24,28,29

Recent evidence has also shown that IL-31 and the IL-31 receptor are highly expressed in prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis.24, 30-34 There is now a wealth of data demonstrating that IL-31 signaling drives itch, is involved in the inflammatory responses in these conditions, and also causes the altered epidermal differentiation and fibrosis characteristic of prurigo nodularis and contributes to skin barrier disruption experienced by patients with atopic dermatitis.24,25

In prurigo nodularis, inflammatory pathways between epithelial surfaces, nerves, and immune cells are connected and amplified via IL-31 signaling.24,26,27 IL-31 is known to induce a set of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines by directly activating a number of immune cells (including myeloid cells, eosinophils, and basophils) and non-immune cells (like keratinocytes and fibroblasts). IL-31 was initially identified as a cytokine produced by type 2 T helper cells and skin-homing memory T cells (CD45RO+CLA+).25 However, this finding was further extended to other type 2 immune cells such as basophils, mast cells, eosinophils, and type 2 innate lymphoid cells.24,35 Beyond type 2 cells, myeloid cells – including monocytes, dendritic cells – and macrophages, can produce IL-31 upon stimulation, indicating that interactions between innate and adaptive immune effector cells and pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to disease severity.24,36,37 The itch sensation that is characteristic of prurigo nodularis is caused by IL-31 signaling between nerve fibers in the skin to the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), spinal cord and brain.26,39

Similarly in atopic dermatitis, IL-31 is produced by both the skin, immune, and non-immune cells and stimulates the sensory neurons expressing the IL-31 receptor, transmitting the itch signal to the central nervous system.26,28,29,40,41 It also stimulates neuronal growth in the skin, possibly resulting in increased hypersensitivity to itch-inducing stimuli in patients with atopic dermatitis.24,42 IL-31 signaling is also involved in inflammation by initiating a feedback loop between keratinocytes, immune and neuronal cells in the skin to all produce – and increase their response to – inflammatory cytokines.26,43-46

Moving the needle in IL-31 research

Galderma has helped to advance the understanding of IL-31 signaling by working together with the scientific community who have delivered meaningful expertise and insights. We are supporting research on how reducing IL-31 signaling can address the pathophysiology and symptoms of prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis.

Disclosure: This advertorial is supported by Galderma.

References

- Pereira MP, et al. Chronic nodular prurigo: clinical profile and burden. A European cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020; 34(10):2373-2383.

- Silverberg JI, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018; 121(3):340-347.

- Joel MZ, et al. Risk of itch-induced sleep deprivation and subsequent mental health comorbidities in patients with prurigo nodularis: A population-level analysis using the Health Improvement Network. E-poster presented at EADV 2023. Abstract available online.

- Brenaut E, et al. The self-assessed psychological comorbidities of prurigo in European patients: A multicentre study in 13 countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019; 33(1):157-162.

- Balieva FN, et al. The role of therapy in impairing quality of life in dermatological patients: A multinational study. Acta Derm Venerol. 2018; 98(6):563-569.

- Janmohamed SR, et al. The impact of prurigo nodularis on quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021; 313(8):669-677.

- Mullins TB, et al. Prurigo Nodularis. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459204/

- Urban K, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of atopic dermatitis in 195 countries and territories: An ecological study from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. JAAD Int. 2021; 2:12-18.

- Silverberg JI. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019; 123(2):144-151.

- Williams KA, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of prurigo nodularis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021; 14(1):67-77.

- Elmariah S, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021; 84(3):747-760.

- Whang KA, et al. Prevalence of prurigo nodularis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020; 8(9):3240-3241.

- Ständer S, et al. Prevalence of prurigo nodularis in the United States of America: a retrospective database analysis. JAAD Int. 2020; 2:28-30.

- Huang AH, et al. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2020; 140(2):480-483.

- Huang AH, et al. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 83(6):1559-1565.

- Kowalski EH, et al. Treatment-resistant prurigo nodularis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019; 12:163-172.

- Zeidler C, et al. Prurigo nodularis and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018; 36(3):189-197.

- Zeidler C, et al. The neuromodulatory effect of antipruritic treatment of chronic prurigo. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9(4):613-622.

- Todberg T, et al. Treatment and burden of disease in a cohort of patients with prurigo nodularis: a survey-based study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020; 100(8):adv00119.

- Pereira MP, et al. Prurigo nodularis: a physician survey to evaluate current perceptions of its classification, clinical experience and unmet need. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32(12):2224-2229.

- Kwon CD, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019; 6(4):97.

- Ständer S, et al. IFSI-guideline on chronic prurigo including prurigo nodularis. Itch. 2020; 5(4):e42.

- Whang KA, et al. Inpatient burden of prurigo nodularis in the United States. Medicines. 2019; 6(3):88.

- Langan SM, et al. Atopic dermatitis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020;396(10253):758]. Lancet. 2020; 396(10247):345-360.

- Ständer S. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(12):1136-1143.

- Bağci IS & Ruzicka T. IL-31: A new key player in dermatology and beyond. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 141(3): P858-866.

- Dillon SR, et al. Interleukin 31, a cytokine produced by activated T cells, induces dermatitis in mice [published correction appears in Nat Immunol. 2005;6(1):114]. Nat Immunol. 2004; 5(7):752-760.

- Wang F, et al. Itch: a paradigm of neuroimmune crosstalk. Immunity. 2020; 52(5):753-766.

- Zhang Q, et al. Structures and biological functions of IL-31 and IL-31 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008; 19(5-6):347-356.

- Sonkoly E, et al. IL-31: A new link between T cells and pruritus in atopic skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:411-7.

- Sonkoly E. Reversal of the disease signature in prurigo nodularis by blocking the itch cytokine. AAAAI. 2022; 149(4):1213-1215.

- Kabashima K, et al. Interleukin-31 as a clinical target for pruritus treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021; 8:638325.

- Kato A, et al. Distribution of IL-31 and its receptor expressing cells in skin of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74(3):229-235.

- Nakashima C, et al. Interleukin-31 and interleukin-31 receptor: new therapeutic targets for atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2018; 27(4):327-331.

- Alkon N, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing defines disease-specific differences between chronic nodular prurigo and atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; 152(2):420-435.

- Datsi A, et al. Interleukin-31: the “itchy” cytokine in inflammation and therapy. Allergy. 2021; 76(10):2982-2997.

- Gibbs BF, et al. Role of the pruritic cytokine IL-31 in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019; 10:1383.

- Takamori A, et al. IL-31 is crucial for induction of pruritus, but not inflammation, in contact hypersensitivity. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):6639.

- Williams KA, et al. Prurigo nodularis: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 83(6):1567-1575.

- Cevikbas F, et al. A sensory neuron–expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell–dependent itch: Involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 133:448–460.

- Xu J, et al. The cytokine TGF-b induces Interleukin-31 expression from dermal dendritic cells to activate sensory neurons and stimulate wound itching. Immunity. 2020; 53:371–383.

- Feld M, et al. The pruritus- and TH2-associated cytokine IL-31 promotes growth of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 138:500–508.

- Rüdrich U, et al. Eosinophils are a major source of interleukin-31 in bullous pemphigoid. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018; 98(8):766-771.

- Raap U, et al. Human basophils are a source of—and are differentially activated by—IL-31. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017; 47(4):499-508.

- Kunsleben N, et al. IL-31 induces chemotaxis, calcium mobilization, release of reactive oxygen species, and CCL26 in eosinophils, which are capable to release IL-31. J Invest Dermatol. 2015; 135:1908–1911.

- Horejs-Hoeck J, et al. Dendritic cells activated by IFN-γ/STAT1 express IL-31 receptor and release proinflammatory mediators upon IL-31 treatment. J Immunol. 2012; 188: 5319–5326.

GL-NMO-2300001